SPECIAL TO THE KOURIER-STANDARD

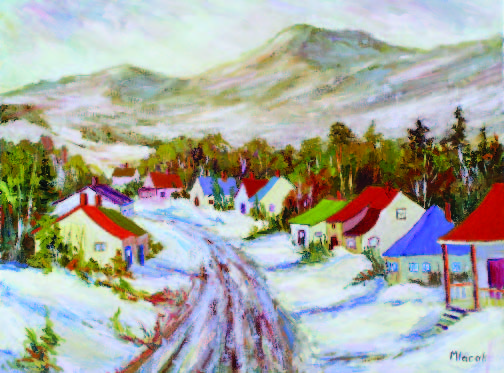

John Mlacak has recently returned from an outdoor painting excursion to the Lac Simon, Chénéville area of Québec. John is looking forward to exhibiting a series of oil paintings based on this trip for the first time at the “Gift of Art”, the Kanata Civic Art Gallery’s 13th Annual Christmas Show & Sale. Visit John’s booth upstairs at the Mlacak Centre, 2500 Campeau Drive, Saturday, November 25 & Sunday, November 26 from 10 am to 5 pm. The Kanata Civic Art Gallery, downstairs, will also be open. Admission and parking are free. Refreshments are available.

Come out and enjoy the beautiful and varied art created by our own regional artists from your local Gallery and do some early Christmas shopping.

Also available in PDF format

Painter John Mlacak’s oil on canvas, titled Rue de l’église, Charlevoix, is just one of 80 juried pieces at the 25th Annual Rideau Valley Art Festival, taking place at the community centre in Westport. The Opening ceremony is 6 p.m. Friday with the show running from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Saturday, Aug. 26, and 10 a.m. to 4 p.m Sunday, Aug.27. Admisssion is $5 general, $4 seniors.

Also available in PDF format.

Manotick Art Association

Featured Artist – John Mlacak

by Rosalie Daly Todd

![Brown-Eyed Susans [Cat. #1257, Sold] Brown-Eyed Susans [Cat. #1257, Sold]](https://www.johnmlacak.com/wp-content/uploads/2005/10/mlacak_j28-110x150.jpg) John Mlacak is an electrical engineer who served for 11 years in local and regional municipal governments, and for three years on the Board of the National Capital Commission. It seems an unlikely background for a highly successful painter of large, bold landscapes and still lifes. But John Mlacak is convinced that there is a common thread through most of his adult activities.

John Mlacak is an electrical engineer who served for 11 years in local and regional municipal governments, and for three years on the Board of the National Capital Commission. It seems an unlikely background for a highly successful painter of large, bold landscapes and still lifes. But John Mlacak is convinced that there is a common thread through most of his adult activities.

To John Mlacak, it has all been about design – designing products for Bell Northern Research (BNR); planning the environment for the (then) new community of Kanata; or creating a work of art.

![Le bois merveilleux [Cat. #1199, Sold] Le bois merveilleux [Cat. #1199, Sold]](https://www.johnmlacak.com/wp-content/uploads/2005/10/mlacak_j15-150x118.jpg) John worked for BNR for 35 years, retiring 11 years ago. While employed at BNR, he also served as March Township’s councilor and reeve from 1966-1974. Next he took a two-year leave of absence from BNR to devote all of his attention to helping to finalize the transformation of portions of several townships into the new community of Kanata.

John worked for BNR for 35 years, retiring 11 years ago. While employed at BNR, he also served as March Township’s councilor and reeve from 1966-1974. Next he took a two-year leave of absence from BNR to devote all of his attention to helping to finalize the transformation of portions of several townships into the new community of Kanata.

![Among Friends [Cat. #1244, Sold] Among Friends [Cat. #1244, Sold]](https://www.johnmlacak.com/wp-content/uploads/2005/10/mlacak_j24-112x150.jpg) Talking to him today, it is still apparent how committed John Mlacak was to Kanata’s planning and design. At the time, he objected to accepted wisdom that Kanata would be just another dormitory suburb for Ottawa. Instead, he supported developer Bill Teron’s vision of a town made up of clusters of individual neighborhoods and communities.

Talking to him today, it is still apparent how committed John Mlacak was to Kanata’s planning and design. At the time, he objected to accepted wisdom that Kanata would be just another dormitory suburb for Ottawa. Instead, he supported developer Bill Teron’s vision of a town made up of clusters of individual neighborhoods and communities.

![Hillside Glow [Cat. #1201] Hillside Glow [Cat. #1201]](https://www.johnmlacak.com/wp-content/uploads/2005/10/mlacak_j16-110x150.jpg) Each community would be inter-connected by pathways to shopping, parks and adjoining clusters. In the center of the communities would be the town centre, the economic and social heart of Kanata – a European-style town square with major shopping, city hall, library and theatre.

Each community would be inter-connected by pathways to shopping, parks and adjoining clusters. In the center of the communities would be the town centre, the economic and social heart of Kanata – a European-style town square with major shopping, city hall, library and theatre.

How successful were they in implementing this vision? Today John Mlacak calls it a “partial success.” Some neighborhoods like Beaverbrook, where the Mlacaks have lived for 40 years, are a showcase for the planning concept. “Most residents can look out their windows and see park land,” he says with obvious satisfaction.

![Avon Lane Chruchyard, New Edinburgh [Cat. #1194, Sold] Avon Lane Chruchyard, New Edinburgh [Cat. #1194, Sold]](https://www.johnmlacak.com/wp-content/uploads/2005/10/mlacak_j14-150x127.jpg)

![Terrain marécageux [Cat. ##1249, Sold] Terrain marécageux [Cat. ##1249, Sold]](https://www.johnmlacak.com/wp-content/uploads/2005/10/mlacak_j26-150x118.jpg) And there is the hockey arena adjacent to the high school, with meeting rooms and library and another 10 acres of land for park use. John fought hard for a local arena, knowing how important hockey and figure skating were to Kanata’s children and the strain on parents who had to drive long distances to take them to practice. He won that battle and a grateful community named the building after him, the Mlacak Centre.

And there is the hockey arena adjacent to the high school, with meeting rooms and library and another 10 acres of land for park use. John fought hard for a local arena, knowing how important hockey and figure skating were to Kanata’s children and the strain on parents who had to drive long distances to take them to practice. He won that battle and a grateful community named the building after him, the Mlacak Centre.

![A côté de l'étang [Cat. #1251, Sold] A côté de l'étang [Cat. #1251, Sold]](https://www.johnmlacak.com/wp-content/uploads/2005/10/mlacak_j27-150x112.jpg) John Mlacak was born in Windsor, Ontario to Croatian-born parents. The Mlacaks were one of many Croatian immigrant families who settled in Hamilton, Windsor or Sudbury to work in the steel, auto and mining industries. John was the third of five children and the first to be born in the new country, Canada.

John Mlacak was born in Windsor, Ontario to Croatian-born parents. The Mlacaks were one of many Croatian immigrant families who settled in Hamilton, Windsor or Sudbury to work in the steel, auto and mining industries. John was the third of five children and the first to be born in the new country, Canada.

![Woodland Fruit [Cat. #1214] Woodland Fruit [Cat. #1214]](https://www.johnmlacak.com/wp-content/uploads/2005/10/mlacak_j17-150x111.jpg) His talent for art did not emerge until 1978 when he suffered a heart attack. During his recovery, he took art classes at the local high school. John laughs today as he describes the experience: “I fought with the teacher! I said ‘just tell me the basic rules. Is it top to bottom, left to right?’ ”

His talent for art did not emerge until 1978 when he suffered a heart attack. During his recovery, he took art classes at the local high school. John laughs today as he describes the experience: “I fought with the teacher! I said ‘just tell me the basic rules. Is it top to bottom, left to right?’ ”

![A côté du lac [Cat. #1222] A côté du lac [Cat. #1222]](https://www.johnmlacak.com/wp-content/uploads/2005/10/mlacak_j19-150x118.jpg) “It took me five years to realize there were no rules,” he says. “That’s when the real difference between engineering and art hit me. Give 100 engineers a problem, and you will get the same answer. And they all will be right. Give 100 artists a problem, and you will get 100 different answers. And they all will be right.”

“It took me five years to realize there were no rules,” he says. “That’s when the real difference between engineering and art hit me. Give 100 engineers a problem, and you will get the same answer. And they all will be right. Give 100 artists a problem, and you will get 100 different answers. And they all will be right.”

John took courses over the years at the Ottawa School of Art. An oil painter by inclination, John took water colours because that was what was generally offered. One of his first instructors, Morton Baslow, was very precise and controlled; his next instructor “just threw the paint on.” It took John a while to conclude: “how you use colour is a function of the paintings you do. How you apply it is a function of style. All are unique to the individual artist; it is impossible to copy another artist’s style.”

![Woodland Harmony [Cat. #1225] Woodland Harmony [Cat. #1225]](https://www.johnmlacak.com/wp-content/uploads/2005/10/mlacak_j20-127x150.jpg) He “learned some tricks from this artist, some from another. They came together somehow and became my own composite style.”

He “learned some tricks from this artist, some from another. They came together somehow and became my own composite style.”

“When I started out, 99 out of 100 paintings I produced were bad; and I wouldn’t sell that one good one,” John says. “Only recently have the number/percentage of good ones increased.”

John says “we” and “us” a lot, referring to his wife, Beth, “who does everything for our little art business but the painting.” Beth spent 20 years as a volunteer for Canadian Parents for French, working with parents and school boards to promote French in the school system. When she passed the torch to others, she concentrated all of her many talents on publicizing and marketing John’s art. He describes her work as a 7-day a week job and one that allows him to concentrate on painting.

Thanks to their successful team effort, John is able to produce and sell 40-50 paintings a year. John admits that it would be very hard to do a quality job without Beth who looks after the preparatory work; decides when and which charity to donate a painting to; turns the visitors’ books from shows into a data base for a Christmas card featuring a new John Mlacak painting each year; and much more. One glance at the professionally written publicity materials she has produced demonstrates that John is not exaggerating her importance.

![Au fond de la forêt [Cat. #1228] Au fond de la forêt [Cat. #1228]](https://www.johnmlacak.com/wp-content/uploads/2005/10/mlacak_j21-128x150.jpg) While employed, John realized that his work would squeeze out his art if he didn’t make a commitment to paint at least once a week. He also realized that taking courses forced him to keep that commitment. “Otherwise, if I let myself get away from it, it would take three months for me to work back to the level at which I was painting,” he says.

While employed, John realized that his work would squeeze out his art if he didn’t make a commitment to paint at least once a week. He also realized that taking courses forced him to keep that commitment. “Otherwise, if I let myself get away from it, it would take three months for me to work back to the level at which I was painting,” he says.

John’s commitment and productivity have increased since his retirement. He works in a basement studio in his Kanata home and keeps a painting schedule that most artists would find unusual. A light sleeper, who has to be at his peak energy level to paint, John operates on what he describes as “two, 12-hour days”. He does chores until mid-afternoon; sleeps for an hour or two; paints from 6 p.m. until about 1 a.m; watches some television; and then manages to sleep.

![Magic of the Woodland [Cat. #1233] Magic of the Woodland [Cat. #1233]](https://www.johnmlacak.com/wp-content/uploads/2005/10/mlacak_j23-150x128.jpg) Lately John has been doing large—four foot by five foot — oil paintings. He has “fun painting large. It gives me lots of room to express myself and the impact of the painting is greater.” Ironically, as his canvases get larger, John finds himself moving in closer to his subject matter. “I focus in now. Instead of doing a sunset, I am doing the sun on a group of trees,” he says.

Lately John has been doing large—four foot by five foot — oil paintings. He has “fun painting large. It gives me lots of room to express myself and the impact of the painting is greater.” Ironically, as his canvases get larger, John finds himself moving in closer to his subject matter. “I focus in now. Instead of doing a sunset, I am doing the sun on a group of trees,” he says.

John paints almost exclusively in oils. They allow him to change, enhance and revise his design. “With water colours, you have to get it right the first time,” he says. “And I never get it right the first time.” Also he feels that his large-size paintings would be hard to do in water colours.

![Les couleurs du marais [Cat. #1248, Sold] Les couleurs du marais [Cat. #1248, Sold]](https://www.johnmlacak.com/wp-content/uploads/2005/10/mlacak_j25-150x118.jpg) John uses Windsor Newton oil paints and Stevenson alkyd medium. His brushes range in size from two to one-half inch. He uses Turpenoid to clean his brushes and just dabs the dirty brush into the jar and brushes the old colour off onto a piece of glass he keeps on his work table. This avoids the opportunity for dirty colours and, as importantly, is a non-toxic way to work, John says.

John uses Windsor Newton oil paints and Stevenson alkyd medium. His brushes range in size from two to one-half inch. He uses Turpenoid to clean his brushes and just dabs the dirty brush into the jar and brushes the old colour off onto a piece of glass he keeps on his work table. This avoids the opportunity for dirty colours and, as importantly, is a non-toxic way to work, John says.

His large canvases are specially-made for him by Artex, with extra wide wood supports in the back because he “likes to beat up my canvases.”

John paints en plein air in Fall and Spring but his move to large size canvases has made that less frequent. Even working with such large sizes indoors presented a problem for John who luckily likes nothing better than solving problems. His solution was to design special brackets to hold his canvas above his work table.

When he begins a painting, John draws his design with pencil on paper that is in proportion to his canvas size. Next he overlays a grid on the paper and then copies the paper grid and design, in pencil, onto his canvas. Finally he uses brushes and India ink over his pencil design on the canvas. For each painting, he paints three to five layers of oils which each dry in one to two days.

When he begins a painting, John draws his design with pencil on paper that is in proportion to his canvas size. Next he overlays a grid on the paper and then copies the paper grid and design, in pencil, onto his canvas. Finally he uses brushes and India ink over his pencil design on the canvas. For each painting, he paints three to five layers of oils which each dry in one to two days.

He paints mostly landscapes but takes a portrait class every five years or so because it “forces me to see.” “You can’t be off with a portrait like you can be with a tree. Portrait painting enforces an artist’s discipline to see relative space, distances and angles. It’s a good disciplinary tool,” John says. John does not often put people in his paintings. He feels, for example, that it is better to add an empty chair or bench: “that way the viewer puts himself into the painting.” When John adds people, he finds that they automatically become the focus of the painting, whether he intends that effect or not.

![Lake Outlet [Cat. #1231] Lake Outlet [Cat. #1231]](https://www.johnmlacak.com/wp-content/uploads/2005/10/mlacak_j22-150x128.jpg) John’s advice to new artists: “take a lot of classes; try different teachers; paint as much as you can. And if you are comfortable, show your paintings to see what response you get from others besides your family and friends.”

John’s advice to new artists: “take a lot of classes; try different teachers; paint as much as you can. And if you are comfortable, show your paintings to see what response you get from others besides your family and friends.”

To John, “selling a painting is an indication of how much people enjoy it. We live in a cash society and value is translated into cash. Selling is the last step in the whole process. It means that someone else enjoys what I enjoy and will give their hard-earned cash for it. It’s a shared experience. I don’t want my paintings sitting in a closet; it wouldn’t be a complete cycle if I couldn’t share them with someone.”

What’s next for John Mlacak and his art? “I want to visit where the Group of Seven painted and get ideas from there. Also there are a lot of subjects in France and Italy … Tuscan hills, backyards in small French towns. I’ve concluded that I need 40 more years to do the things I want to do.”

What’s next for John Mlacak and his art? “I want to visit where the Group of Seven painted and get ideas from there. Also there are a lot of subjects in France and Italy … Tuscan hills, backyards in small French towns. I’ve concluded that I need 40 more years to do the things I want to do.”

Alex Munter

The Ottawa Citizen

August 20, 2005

Is it the Glebe, the only neighbourhood in recent memory to elect a poet to city council? Or maybe it’s a rural village like

CREDIT: Bruno Schlumberger, The Ottawa Citizen Unlike many Ottawa artists, John Mlacak of Kanata, a retired engineer and politician, is in the lucky position of not having to worry about finances. He has his pension, and his wife, Beth, looks after selling his work. 'I have a unique advantage over other artists. We have two people-years, seven days a week.' Though Ottawa arts incomes are a little higher than the Canadian norm, they're still one-quarter less than the overall labour force average.

Manotick, which has a highly-visible artists’ association? Or could it be a tree-lined suburb like Rothwell Heights or Qualicum, where numerous retirees and stay-at-home parents pursue their vocation? Or how about Vanier, its lower rents and affordable homes perhaps attractive to starving-artist types?

Kelly Hill knows the answer to that question. But he’s not telling. At least not until late September.

That’s the date he’ll be revealing the answer to a national quiz his arts consulting company has launched.

Mr. Hill has crunched the numbers, neighbourhood by neighbourhood, province by province, to see which Canadian postal codes have the greatest concentration of full-time artists or, as he puts it, “people who work at an arts occupation more than any other occupation.”

Peter Honeywell, executive director of the Council for the Arts in Ottawa, is putting his money on the Hintonburg/Westboro area.

He points to the virtual overnight success of Westfest, the spunky, funky, arts festival that has gone from mere idea to community sensation in just two years. “The business community there is getting behind it. They see the benefit of paying artists to come in and do festivals.”

“People visit Westfest one weekend, notice some of the shops that are in the area, don’t have time to go to them, and then go back another week.

“It’s what could happen in every community.”

Mr. Honeywell says the West Wellington area has a critical mass of artists, drawn in part by a broad range of housing types. A popular annual walking tour of artists’ studios is slated for mid-September.

Christine Tremblay predicts that if her part of the city — the suburban east end — doesn’t win the crown yet, it will soon.

“We’re at that point where it’s busting out, everyone wants to go to the next level and that energy is there,” says Ms. Tremblay, who runs Arts Ottawa East.

“We’re encouraging people to take the next step — helping them go a bit more professional.”

Probably nothing illustrates that better than the enthusiasm over the east-end arts facility, which the city plans to open in Orleans in 2008. Arts groups were joined by businesspeople and community leaders in pushing for the project.

Mr. Hill’s contest comes just as the City of Ottawa has released a discussion paper about its arts investment strategy. There is to be extensive consultation about the document this fall.

The discussion paper confirms local artists’ long-standing complaint that Ottawa’s municipal government invests far less in arts and culture than do most Canadian big cities. We come seventh out of seven.

But the document’s most dramatic revelation is actually how poorly we fare in terms of provincial and federal funding, too.

That supposedly nasty right-wing government in Alberta puts seven times as much into Calgary’s and Edmonton’s local arts scenes as the Ontario Arts Council contributes to Ottawa.

Closer to home, Toronto gets three times as much from Queen’s Park as does Ottawa.

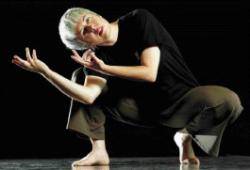

CREDIT: Wayne Cuddington, The Ottawa Citizen Dance choreographer Anik Bouvret makes ends meet by working part-time in administration at the National Gallery.

It’s the same story at the federal level. We’re essentially tied for dead last with Calgary, which at least has Ralph Klein looking out for it. Vancouver is the big winner in federal local arts investment.

Add up the support for the arts from all three levels of government and Montreal and Vancouver respectively rake in $46 and $44 per capita. The other cities are in the mid-$20 range.

In Ottawa, dead last, it comes out to $10 per person per year — basically, one cent per day from each level of government.

City statistics show that, for each dollar the City of Ottawa puts into the arts, more than $10 comes from other sources, including fundraising and private investment.

And, there again, we are at the back of the class. That multiplier effect is much bigger elsewhere.

During the city’s last round of extensive consultations on the arts, leading to the 2003 adoption of the arts and heritage plan, American academic Richard Florida made quite a splash when he visited Ottawa.

Mr. Florida, a professor of regional economic development at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Mellon University, has looked at U.S. cities that are prospering and those that are falling behind.

He says the key to economic success is the presence of a “creative class” that includes scientists and engineers, poets and novelists, artists, entertainers, actors, designers and architects.

Their presence, he argues, is a harbinger of economic success. In this post-industrial era, his research shows that the greater the concentration of such people, the better a city will do economically.

“Creativity has replaced raw materials or natural harbours as the crucial wellspring of economic growth,” he says.

Canadian arts expert Kelly Hill agrees that “the presence of artists and a lively artistic sector builds community cohesion, creates an opportunity to interact and generates economic benefits.”

And he shares Mr. Florida’s conviction: cities that neglect arts and culture won’t just be sadder places to live, they will also hurt their future prospects for prosperity.

Statistics Mr. Hill compiled for the Canada Council for the Arts show that Ottawa has a much lower share of its workforce engaged in the arts than most large Canadian cities and, in fact, is rivalled by many smaller centres.

Places like St. John’s, Halifax and Victoria have, proportionately, many more artists. Ottawa is comparable to Winnipeg and Kingston, but even that stat is misleading. Those cities don’t have major federal arts institutions like the National Arts Centre bumping up the number.

The problem is, local artists generally don’t have access to those venues. They don’t belong to Ottawa the town, they belong to Ottawa the capital.

After all, if you’re a local artist, you can’t wander over to the National Gallery and hang your work there.

Mr. Hill says your mother was right when she warned you there wasn’t much money in the arts. Though Ottawa arts incomes are a little higher than the Canadian norm, they’re still one-quarter less than the overall labour force average.

And that means many artists, like contemporary dance choreographer Anik Bouvret, get other jobs to make ends meet.

“Being an artist is very difficult financially. At 36 years old, I’m hopeful at some point I’ll be able to do it full-time, but I’m also realistic. It hasn’t happened so far.”

But Ms. Bouvret, who grew up in Orleans and returned there after completing a dance degree in British Columbia, considers herself lucky to have found part-time employment at the National Gallery.

“At least my administrative job is quite inspiring because I am in an artistic environment.”

Ms. Bouvret mostly practices her craft downtown at venues like La Nouvelle Scene or at dance festivals in other cities. But she too has noticed the burgeoning arts scene in the east end.

“A window has opened,” she says. “Now is the time to bring the arts into the community.”

Peter Honeywell, of the Council for the Arts, says Ottawa’s lack of venues for performing arts has chased many of the city’s best and brightest away.

Our strength has tended to be in sectors where artists can work independently out of their homes, like writing or the visual arts, he says.

He’s talking about people like John Mlacak of Kanata.

An engineer by training, Mr. Mlacak originally got into art for therapeutic reasons. “After my heart attack in 1978, I took an art class and I found I enjoyed it.”

“It took me about five years to find out there aren’t any rules to art,” he said.

“I discovered the difference between an artist and an engineer. If you give a problem to 100 engineers, you’ll get one answer and it’ll be right. If you give a problem to 100 artists, you’ll get a hundred different answers and they’ll all be right.”

After his retirement in 1994, Mr. Mlacak delved into art full-time. He now spends five hours a day painting, mainly in oils but occasionally in watercolours and pastels. His paintings, generally landscapes, are widely exhibited locally. He sells about 50 per year.

Mr. Mlacak, 69, says his third career bears a lot of similarities to his first two jobs, in engineering and local politics. “It’s all been design work. I haven’t fundamentally changed what my nature is.”

Mr. Mlacak admits his pension gives him the freedom to pursue his art full-time. He attributes much of his success to his wife, Beth, who handles the marketing and promotion of his work. “I have a unique advantage over other artists.

“We have two people-years, seven days a week.”

As more and more energetic, educated baby boomers are liberated from their careers, one wonders how many will follow Mr. Mlacak’s example and unleash the artist within.

Who knows?

Maybe Ottawa’s most creative neighbourhoods will become the ones with the highest concentration of young seniors.

But, for now, Mr. Hill drops a small hint about the kind of postal codes that will make his top-10 list: “they’ll be funky neighbourhoods that a lot of people are drawn to.”

To enter the contest, go to www.hillstrategies.com.

And just a note to my regular readers — I am still researching the subject originally slated for today’s ‘Neighbourhood Faces’ column, divisions within rural Ottawa. That piece has been delayed to the fall, closer to the date of the rural summit.

Alex Munter is a visiting professor at the University of Ottawa and former Ottawa city councilor. E-mail him at amunter@uottawa.ca.

Next Week: A visit to Ottawa’s emerging gaybourhood.

© The Ottawa Citizen 2005

Also available in PDF format.

![Yardscape, Avon Lane, New Edinburgh [Cat. #1193] Yardscape, Avon Lane, New Edinburgh [Cat. #1193]](https://www.johnmlacak.com/wp-content/uploads/2005/10/mlacak_j13-150x119.jpg)